PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) has reached 30 million players worldwide, according to data released by producer Bluehole, with Chinese players accounting for 46%. However, PUBG’s anti-cheating tech provider, BattlEye, also released data showing that 99% of accounts banned for cheating are from China.

Programmers, sales platforms, and agents who promote and sell illegal mods make up a tight industry of plug-in (also called mods, add-ons, bots; anything where software assistance affects gameplay in order to gain an unfair advantage over opponents) sales, where some hundreds of programs are distributed and sold for high prices, generating what’s called “gray income”.

The Capabilities of Cheating

PUBG is a multiplayer online battle royale game that drops 100 players onto a deserted island where they must scavenge for weapons and equipment to kill each other and survive as long as possible. The number of players diminishes as they are killed, and the map grows smaller and smaller until the last player standing is declared the winner, wherein they receive a screen declaring, “Winner winner chicken dinner”.

Unlike other types of games, shooting games rely heavily on internet latency. The calculation required to judge whether a bullet hits an object needs to be done quickly, so it’s usually done on the client computer (locally) and the result is then sent to the server. A frequent user of plug-ins, Chen Feng (a pseudonym), explained, “The best-case scenario for a game is that all the calculations are done on the server, but it’s not done that way in practice. The more things that are done locally, the more there is for plug-ins to work with.”

The principle behind plug-ins isn’t difficult– it’s essentially tampering with the game program data. Programmer “Wild Dog” said, “The principle is divided into local tampering and upload data tampering. Local tampering is divided into two categories, tampering with game modules and memory modifications.”

For a “remove weeds” plug-in, for example, the essence is to change the game’s color module that corresponds to grass from green to transparent, so grass on the ground will disappear. For a real-time display like “see-through” (aka, ESP), you need to modify the memory. The plug-in achieves the see-through effect by reading the location of players/items in the memory and marking them. “After loading the game, a lot of parameters or data will be temporarily stored in memory, so a plug-in can go into the memory and tamper with the data,” explains “Wild Dog”.

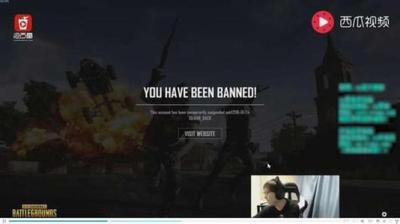

The real trouble for plug-ins is getting past the anti-cheat system. There are two systems for PUBG, one is Valve Anti-Cheat (VAC) and the other is BattlEye. The working principle behind BattlEye, for example, is that it monitors memory tampering (also called injections) and scans the hard drive for suspicious plug-ins. If BattlEye finds one, it will upload the plug-in to the cloud and all players using that plug-in will be banned. Programmers usually disguise the plug-in as a driver or will hijack the anti-cheat system, allowing the plug-in to run “safely” on the player’s computer.

The core of shooting games lies in a player’s marksmanship and technique, so aimbots, ESP and other plug-ins have seriously undermined the fairness of competition.

For live games, there’s no lack of plug-in camouflage technology. Well-known streamers like 55开and 蛇哥 among others are well-known for using plug-ins. Recently, a journalist was able to meet with a cheating streamer and saw that a game fully outfitted for cheating includes both ESP and automatic targeting (aimbot). There are a variety of settings in automatic targeting, such as “don’t aim while falling”, “configure aiming location”, and even “proactive auto-aim” among other professional-level manipulations. Viewers cannot, therefore, discern whether a streamer is cheating simply by watching the live stream.

|

| Example of ESP plug-in |

Mysterious Programmers and Active Agents

In the plug-in industry, each position has a clear division of labor. The programmer is responsible for plug-in development and routine maintenance updates, the sales platform is responsible for setting up “paywalls”, and the agent is responsible for recruiting lower agents and selling plug-ins.

Chen Feng said, “China’s plug-in industry is much more developed than it is abroad because there’s a lot of systemization, the industrial chain has grown a lot. Generally, you don’t know who the true programmer of a plug-in is.” Creating plug-ins is in itself copyright infringement, so plug-in programmers tend to stay anonymous or use codenames to avoid legal risks.

As explained by programmer “Wild Dog”, there are some “network authorization platforms” for “new plug-in users” that effectively connect programmers, sales, and users. The platform, on the one hand, provides the plug-in programmer with the SDK (software development kit). The programmer only needs to add a function to the plug-in program to establish a paywall. Users need to register, log in, and buy a time card to use the plug-in. The sales platform provides various types of time cards, including daily cards, monthly cards, membership cards, and so on. Sales agents will buy a large number of cards wholesale, and then the cards will be sold for a profit layer by layer. Agents also make money by charging agency fees.

“Wild Dog” also said that there’s often fraud in the plug-in industry. Some agents will lure prospective agents by saying you can make tens of thousands a month by selling plug-ins. They then charge these new agents fees of a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, developing their own production lines.

A journalist posed as a prospective agent as an excuse to communicate with the head plug-in sales person at an agency. The sales person said that buyers only pay a 100 RMB agency fee to agents (about $16 USD), and they then make money by buying cards from the agency and selling them on the sales platform, a profit margin of about 30-40 RMB.

Profit for sellers is considerable– the kind of plug-in that streamers use costs 6000 RMB a month ($945 USD). If you just want the ESP/see-through plug-in, it costs 2600 RMB per month ($409 USD) and a “fully functional” plug-in costs 3500 RMB per month ($551 USD). Because there is no fixed cost for plug-ins, plug-in sales have become a kind of pyramid scheme. Compared with mysterious programmers, plug-in agents are particularly rampant. The head plug-in sales person said their method is to develop publicity on social media, establish a group that can be drained, and, “in one day you can earn enough to pay a month’s worth of living expenses.”

QQ is the primary channel for agents. A quick Weibo search for “PUBG assistance” comes up with plug-in groups that lead to agency websites, forums, and group QQ numbers. Publicity for agent services is even making it into the game. On the February 6thlist of top ten PUBG players, four players had names that were the QQ group numbers for plug-in sellers.

Many plug-ins also contain Trojans. Since plug-ins need to modify game data, they require users to turn off their anti-virus software. Even if the anti-virus warns users that the file is a Trojan, users may think it’s a false positive and ignore it. Some of these Trojans turn users’ computers into mining rigs. Recently, Tencent Computer Manager released news that some PUBG plug-ins had hidden mining Trojans that mined for HSR (Hshare Coin, a cryptocurrency worth about $13 each). Since the hardware requirement for PUBG is higher than for other games, players’ computers become excellent mining rigs.

Plug-in “Manufacturing”

On January 30, blogger @灵石路黄师 released a screenshot saying that the German-based plug-in “manufacturer” Bossland was eyeing the popular game PUBG and had developed a plug-in for players to buy and download.

The reason why Bossland is called a “manufacturer” is because Bossland Company developed cheats for many of Blizzard Entertainment’s games, leading to an eight-year litigation tour. Since Bossland is allowed to continue selling products until the court makes a ruling, it delayed trial by making counterclaims. The lawsuit finally went to the German Federal Court of Justice in 2015, where Bossland’s hacks were banned from sale in Germany. In 2017, they were ordered by a court in California to pay Blizzard $8.6 million USD, who alleged that each of the 42,818 hacks they sold in the USA constituted copyright infringement (from PCGamesN).

Despite the mass-ban in Germany, Bossland hasn’t closed shop. They have a large number of users who purchased life-long licenses for some of their products, and even though they can’t advertise their software on websites or social networks, they send software development information to their old users via email subscription.

There is a website in China specializing in the sale of Bossland hacks where you can download their latest PUBG plug-in, “Unknown Buddy”. @灵石路黄师 says the owner of this site is a Bossland forum moderator and is a Chinese Bossland agent.

An investigation into the site found that the domain name belonged to a person with the surname Zhang (equivalent to the surname Smith in the West), and was approved on January 29, 2018, just before the Bossland email was sent out.

According to reports, Bossland plug-ins and other, ordinary plug-ins are mostly the same—the main function is to provide ESP and automatic targeting. However, users in the plug-in exchange group believe that because Bossland created the plug-in, the PUBG anti-cheat systems will have trouble detecting it, making it safer to use.

The Bossland plug-in claims that in addition to providing in-game functions, it also protects users from bans. According to reports, when the anti-cheat system begins banning on a large scale, Bossland will use a key to remove the plug-in from players so as to avoid account closure.

On November 22, 2017, Tencent announced a PUBG Chinese server. Players hope that Chinese game manufacturers can crack down on plug-ins. A representative from Tencent in charge of problems related to Bossland plug-ins said that since the domestic server hasn’t formally launched yet, there are no specific measures in place for PUBG plug-ins. They will wait until the domestic server is online and if the plug-in phenomenon is serious, Tencent will take measures to combat it.

Safeguarding Game Company Rights Isn’t Easy

iDreamSky’s legal manager, Lin Zhicheng, told reporters that creating mods and plug-ins for games is a criminal act of copyright infringement on computer software and information systems. In theory, a game company can join forces with the police to crack down. However, local companies may not be able to sue because Bossland is located offshore. (Bossland’s CEO made this argument when it was brought to court in the US by Blizzard, stating that a Californian court will have no jurisdiction over his company as they have no official business in the US.) Even if the prosecution wins the case in China, due to geographical jurisdiction, the German government will be unable to enforce the ruling.

Even if the plug-in manufacturer is in China, defending the rights of the game company isn’t easy. Lin Zhicheng said plug-in programmers use the Internet to hide, and it’s difficult to locate them. Picking up agents selling the plug-in is just punishing the act of one person, and it’s difficult to rely on civil evidence alone. Websites that sell the plug-ins are akin to “shell companies” (no fixed assets, no fixed place of business, no fixed corporate personnel) when they register, making it difficult to find the criminal subject.

However, some companies are still trying their best to institute regulatory measures. Another shooting game, CS:GO, has been cracking down on plug-ins. Their developer, Valve, not only introduced the advanced anti-cheat system Valve Anti-Cheat (VAC), but also joined the manual reporting and review system Overwatch.

The Overwatch system uses qualified and screened community members to examine and judge whether or not a player who has been reported too many times was cheating by watching videos of the player’s games. If VAC discovers a player is cheating, that player will receive a lifelong ban. The Chinese domestic CS:GO servers even joined together with Ant Financial to use their Sesame Credit system (a social credit system) to implement real-name authentication to counter cheating. Once your account is banned, it’s as if your identity is banned, which greatly increases the cost of using plug-ins for cheating.

In addition to using external measures, there are companies who try to crush plug-in groups from within. When dealing with Bossland, Blizzard appeared to offer “amnesty” to the creator of the Heroes of the Storm plug-in “Stormbuddy”. Blizzard pressured them with a formidable lawsuit, but they offered an agreement—Blizzard would drop the suit in exchange for all the Stormbuddy source code, which the creator accepted.

In Lin Zhicheng’s opinion, rights protection is always merely temporary. He explained, “Why does the game have illegal plug-ins? Because the game is flawed. Investigate to close the loopholes, and plug-ins will become useless.”

Source: 17173.com, originally published in Southern Metropolis Daily (南方都市报); translated with additional information by Johanna Armstrong for Youxi Story.

CHINA NUMBA ONE!

LikeLike

Yeah China number one for cheating and very small pee pee

LikeLike

well done china you killed a fun game

LikeLike

The good old Wild West knew what to do with Cheaters.

LikeLike

Money pushes all this

LikeLike

#RegionLockChina

LikeLike

Do you know why love PUBG? Because it is one the best games in the world!

LikeLike